|

| Mmm, donuts. |

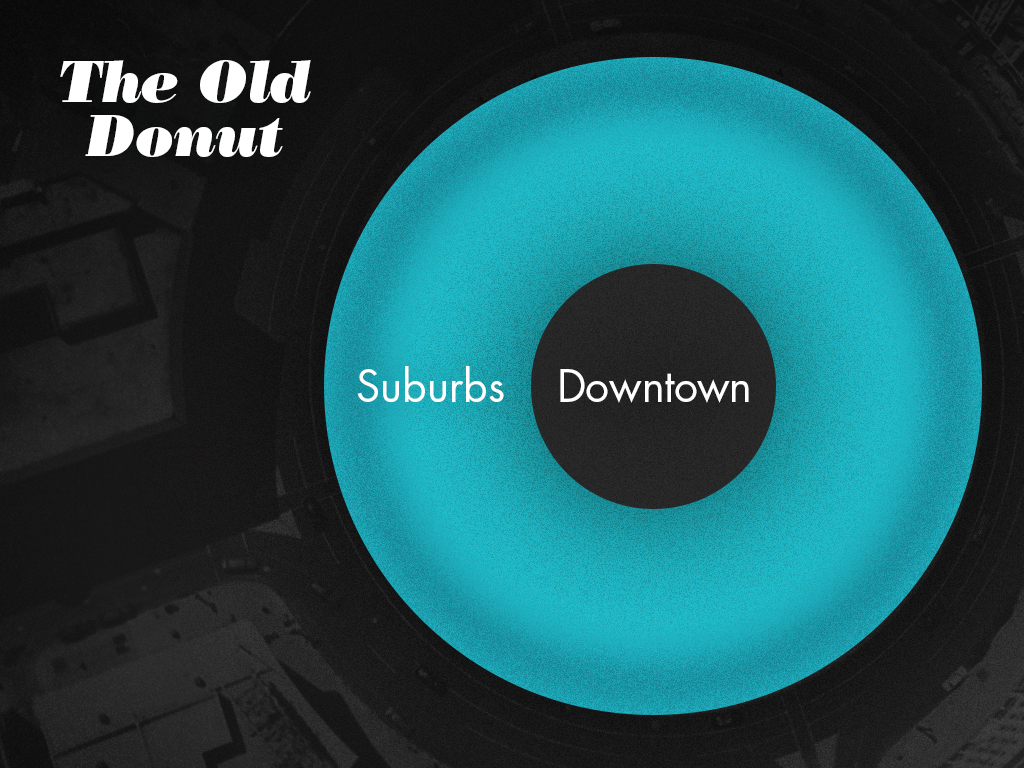

Renn then categorized the current development trend of many cities with gentrifying and revitalizing downtown districts, calling it the "new donut" paradigm. Some urbanists have attributed some of the effects of this new paradigm to the existence of traditional zoning in cities, claiming that existing zoning restraints effectively renders parts of cities unable to address the needs for increasing housing or development needs. As evidenced here in Houston, and recently in Minneapolis, among many other cities, Renn notes that:

Filling in the hole became every city’s mission. Pretty much any city or metro region of any size has pumped literally billions of dollars into its downtown in an attempt to revitalize them. This took many forms ranging from stadiums to convention centers to hotels to parking garages to streetcars to museums and more. It’s popular today to subsidize mixed use development with a heavy residential component.Mmm, donuts. In Houston, when you discuss donuts, the topic rapidly shifts to Shipley's. It's Shipley's versus the rest of the world here, although Dunkin Donuts is making a push for a Houston presence. I'm not really sure how fried breakfast foods ended up being an analogy for discussing urban development, but they're both things I enjoy, so I don't mind it at all. And, since it's now fall, all this talk about donuts brings back the memories of Blakes Cider Mill in Armada, Michigan, sitting in the middle of an apple orchard, chowing down on freshly fried donuts washed down by fresh-pressed apple cider.

|

| Courtesy of Urbanophile.com |

|

| Courtesy of Urbanophile.com |

In response to Renn's "new donut" model, Chicago's Pete Saunders offered thoughts on his Corner Side Yard blog. Saunders is clear to say that he is "persuaded that addressing problems of segregation and inequality cannot be done solely through the elimination of exclusionary zoning practices." Saunders focused his thoughts around the use of zoning and how it has shaped cities. He includes that:

One response to this phenomenon, and to the pressures placed on in-demand city neighborhoods undergoing gentrification, is zoning reform that would eliminate exclusionary zoning practices by municipalities. Many urbanists and economists, and a growing number of other social scientists, say that the elimination of exclusionary zoning policies would generate a greater supply of housing, reduce housing costs and reduce the kind of wealth and social inequality that plagues our nation.Saunders says, "I am in the minority on this, but such a policy would be fraught with unintended consequences. Advocates of this policy idea are wrong." He's right, there's not too many scholars that would agree with him. But some analysis in the DC Metro area lends evidence to the successes of inclusionary zoning. Saunders continues:

My thinking on this is ripe for academic study and scrutiny. I hope at some point someone picks this idea up and tests its veracity. In the meantime, the best way for me to explain my reasoning is through a thought experiment.In opposition to Saunder's viewpoint, professors Benjamin Powell and Edward Stringham note in their Florida State Law Review essay that:

The real problems causing the affordability crisis are regulations that prevent increases in the supply of homes. Eliminating restrictive zoning regulations will give consumers more choice and make housing more affordable. For those who truly care about making housing more affordable, price controls are not the answer.There's more. The argument is that zoning restriction "continues to constrain, the supply of low-income housing." Others tend to agree. But do their claims really hold up in Houston? In some areas it may, but it still remains true that few would want to live in a neighborhood that is unsafe or lacks good schools or public services.

I'd like to throw Houston in the running to test some of these claims surrounding zoning reform. Before anyone claims that eliminating zoning will help alleviate a need for housing supply or segregation, we've got to look at a control, much like in a scientific experiment. The only problem is, neighborhoods don't operative in a vacuum, so scientific principles can't be used here. Zoning reformers claim that eliminating zoning in cities would do three things: 1) increase housing supply, 2) decrease housing costs, and 3) reduce the wealth and social inequality that is so prevalent in our country.

Regarding Houston, I think we can falsify all these claims. Our city has been and continues to be a very segregated city. Take a look for yourself at the geography of Houston's low income population, especially toggling between 1980 and 2010. It doesn't look like much has changed. Or, take a look at our census data mapped out. At first blush, it doesn't look like an absence of zoning can simply fix housing ills.

As I've already noted previously, it's not unnoticed that at the same time Houston boasts as the most diverse city in the country it is also one of the most segregated cities in the country. That fact wasn't lost on Tony Perrottet, who chronicled his trip to Houston in Smithsonian Magazine. He noted that, even though Houston claims great diversity, "There are, however, some arguably ominous trends. Perhaps the most disturbing is that, according to the Pew Research Center, Houston is the most income-segregated of the ten largest U.S. metropolitan areas, with the greatest percentage of rich people living among the rich and the third-greatest percentage of poor people among the poor." In that same article, Dr. Stephen Klineberg of Rice University's Kinder Institute warns that “ Houston is on the front line, where the gulf between rich and poor is widest. We have the Texas Medical Center, the finest medical facility in the world, but we also have the highest percentage of kids without health care. The inequality is so clear here.”

Last week the Houston Chronicle's Gray Matters blog featured a review, Divided We Sprawl, of Cort McMurray's essay in Houstonia Magazine. McMurray, in addressing Houston's sprawl and inequality, provided some great perspective, saying:

The problem isn’t sprawl. It’s the reasons for the sprawl. In Houston, a city where civic boosters regularly tear their rotator cuffs slapping themselves on the back in congratulations for Our Rich Diversity and Amazing Quality of Life, sprawl is driven not by the search for new opportunities, but by the conviction that Our Rich Diversity and our Amazing Quality of Life are mutually incompatible.People will decry how affordable housing is here in Houston. Please visit and see for yourself just how expensive housing actually is, at least within a 5 mile radius of downtown Houston. Sure, housing is still affordable in Houston in general, just not in many of the traditional neighborhoods where one may first want to live. It's now become a reality that middle income families and workers are not able to find affordable housing. Houston's housing is getting more expensive, and it's forcing families to move to outlaying areas, while higher income families and individuals are moving into the city's core. Take a look at this map showing the median sale price of homes within the Houston area. It's certainly darker in the middle, with Houston's highest prices in the Heights, Montrose, River Oaks and Memorial areas.

|

| 2013 Median Housing Prices - Houston Chronicle |

This leads us back to the "donut" and "new donut" paradigm illustrations. Houston's inner core, at least that area within the I-610 loop, predominantly west of I-45, makes up most of the "new donut" downtown area, even though Houston's currently gentrifying and historically vibrant neighborhoods lie just outside of its downtown district. Our "Inner Suburbs and Inner Core" portion of Houston (think Alief, Sharpstown, Southwest and Southeast Houston, Northside, Acres Homes) is continuing to age, and is evidenced when we look at home sale prices. Naturally, then the newer homes in the "Collar Counties" (think Sugarland, Cinco Ranch, The Woodlands, Kingwood) attract families and professionals looking for new housing. That comprises Houston's "new donut" paradigm.

So, does the "donut" analogy hold true in Houston? More or less, I would say so. At the very least, we are in the late transition stages of moving into the "new donut" paradigm. And we can testify that a lack of zoning does not mean that housing supplies will rise, housing costs will decrease, that there will be enough of a diversity of housing, or that societal inequalities will be remedied. If a reformed approach to zoning is to be a fix for responding to the challenges of the Inner Suburbs and Urban Core periphery, then don't look to Houston. Our lack of zoning certainly hasn't fulfilled the housing predictions of zoning reformers. I hope that at the end of the experiment, Houston is not the precipitate.

If you wanted to take this breakfast thing even further, some might say that the Houston area's development is concentrated in more of a wedge, or scone if you will. (For the record, scones are definitely the Rodney Dangerfield of the breakfast pastries. They are far less respected than they should be.) This wedge or scone analogy might be a better fit when looking simply at the city of Houston proper instead of the larger Houston metropolitan area, and would comprise of the area from downtown Houston, including Montrose, the Heights, River Oaks, Memorial, and extending into Harris and Fort Bend Counties to Cinco Ranch area, and out to Katy.

Now if we could just find a city that had very small nooks and crannies of disinvestment among a spread of development, we might have ourselves an "English muffin"-type paradigm. Okay, that's a bit too far. After all, it's breakfast, and I'm hungry. I'm going to grab a donut. Or bagel. Or scone. Or English muffin. And, maybe I'll just wash it all down with a Minute Maid.